Bordeaux: classifications and rankings

Author: Berry Bros. & Rudd

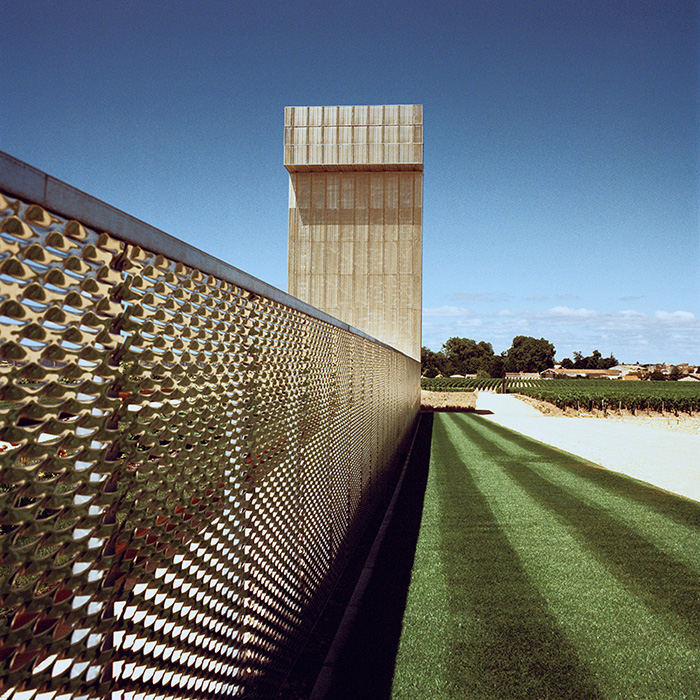

Ch. Gruaud Larose. Photograph: Jason Lowe

In 1855 the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce drew up a new classification of the red wines of the Médoc and the sweet wines of Sauternes and Barsac, which they presented at the Universal Exhibition in Paris. The red wines were ranked by the price they commanded into five levels, or ‘crus’, with Chx Haut-Brion (the only wine included from outside the Médoc peninsula), Lafite, Latour and Margaux occupying the top tier.

The sweet whites were split into two levels, first and second – but with Yquem above the list as the sole Premier Grand Cru.

The only significant change to the 1855 list was in 1973, when Ch. Mouton-Rothschild was promoted from Second- to First-Growth status: that took a Presidential decree.

The classification is now over 150 years old, so has some anomalies, with châteaux like Palmer (Third Growth), Lynch-Bages (Fifth) and Pontet-Canet (Fifth) among others, performing above their supposed status; however, few people would argue with the status of the top tier.

If the exercise were to be repeated – based again on market price – there would, though, be surprisingly few changes. That said, the market recognises a clutch of ‘Super-Seconds’ that can challenge the Firsts in price. These include Léoville-Las Cases, Léoville-Barton, Montrose, Palmer, Cos d’Estournel….

(If anyone offers to sell you a case of Third-Growth Ch. Dubignon, refuse: the wine is indeed on the 1855 list, but its land was sold off decades ago to other châteaux.)

Exactly a century after the Médoc list, in 1955, St Emilion introduced a classification based on the results of a tasting panel. Any property producing wine of St Emilion Grand Cru status (a status attained simply by a slightly higher alcohol level and lower yield than straightforward AOC St-Emilion) could apply, and potentially be classified – in ascending order of merit – Grand Cru Classé, Premier Grand Cru Classé B or Premier Grand Cru Classé A. This classification is reviewed (notionally) every decade, with the possibility of promotion and demotion, the most recent update being in 2012.

Graves decided to follow suit in 1959, with both red and dry white wines having the chance to become Cru Classé. Thus far, there has been no review of this classification other than the addition of Haut-Brion white in 1961.

A point to note is that all these Bordeaux classifications, with the exception of the relatively lowly St-Emilion Grand Cru, are not enshrined in the AOC rules, unlike Premier Cru and Grand Cru vineyards in Burgundy and Chablis.

Note, too, that in Bordeaux it is the châteaux that are ranked, but in Burgundy it is the land. A Bordeaux château can expand its vineyard (as long as it buys land of the same AOC) without changing its classification – and some have done just that. In Burgundy, by contrast, it is forbidden to expand a Grand Cru by even a row of vines.

Find out more about Bordeaux on bbr.com, including information on the Bordeaux 2015 en primeur campaign.