The enduring power of print

Author: Simon Berry

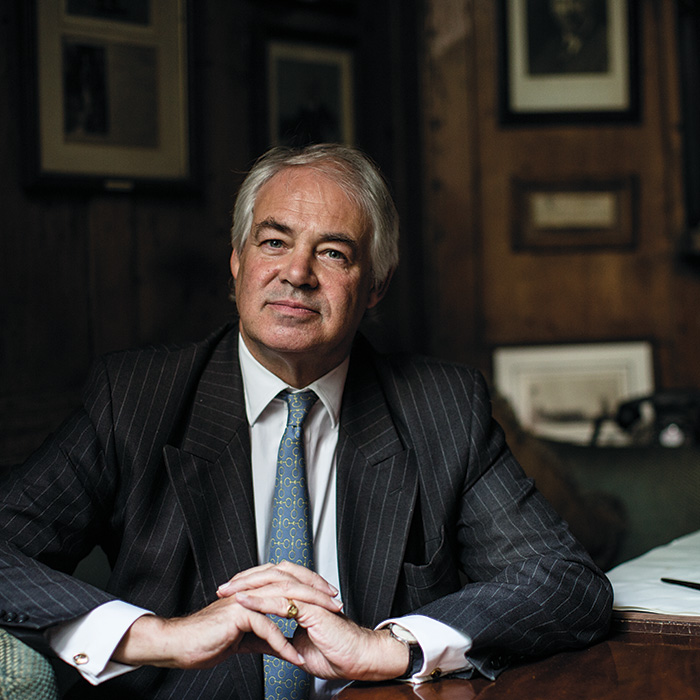

Simon Berry in the Parlour. Photograph: Elena Heatherwick

When, in 1954, my father decided that Berry Bros. & Rudd should publish a regular magazine, it was a pretty revolutionary thought.

Through the telescope of history, this seems strange. But our perspectives have changed over the past 60 years. When I took over editing it, some 30 years later, the magazine had a very dated feel to it – published under the title Number Three Saint James’s Street (not the snappiest), illustrated withline drawings or black-and-white white photographs, and with a never-changing front cover apart from the colour, it resembled a parish magazine more than a modern wine publication.

But back in 1954, it was arguably the first wine magazine in the world. Decanter hadn’t been invented, let alone Wine Spectator, The Wine Advocate, The World of Fine Wine or Le Pan. No national newspapers featured regular wine columns, and television coverage of wine stopped at Johnnie Cradock secretly knocking back a glass or two off camera while Fanny whisked something up in a bain-marie.

The initial plan of four issues a year (spring, summer, autumn and winter) never materialised. Instead Number Three (as it became known) was published to coincide with our tiny “waistcoat pocket-sized” price list, in March and October. It complemented the price list wonderfully, adding context, opinion, tasting notes, maps and suggestions to the rather stark black-and-white “laundry list” that had almost come to symbolise Berry Bros. & Rudd’s quirky tradition.

My father kept a proprietorial eye on the proceedings, but the real work was done by Herbert Hunter, who was the “publisher”, and Edward Owen, who wrote most of the articles. It was Hunter’s idea in the first place: a stalwart of the early days of advertising, he had a business producing private magazines for companies (although I never knew of any other clients apart from Berry Bros. & Rudd). But in the days before Desktop Publishing, when you still had to deal with galley proofs, camera-ready artwork and last-minute editing involving Tipp-ex and a Stanley knife, you needed people like Hunter to take you from concept to actuality.

Edward Owen was even more integral to the success of Number Three. An old-school journalist, albeit far from the Lunchtime O’Booze school of hard investigative reporting, he was a native of Guernsey (“The Bailiwick”, as he called it) and The Times’s Channel Island correspondent. Twice a year, however, he would take the ferry from St Peter Port, and come and interview my father. They would discuss relevant topics for the editorial piece that always kicked off the publication, “From the Inside” – very often something which had emerged from a customer’s letter, or something that had caught my father’s eye in a wine-related newspaper article. They would choose a wine area to highlight – in the first edition they picked: “Sherry: the Wine for All Occasions” – and any other subject about which our customers might be concerned: decanting, or how to make a Moselle or Champagne cup, for example.

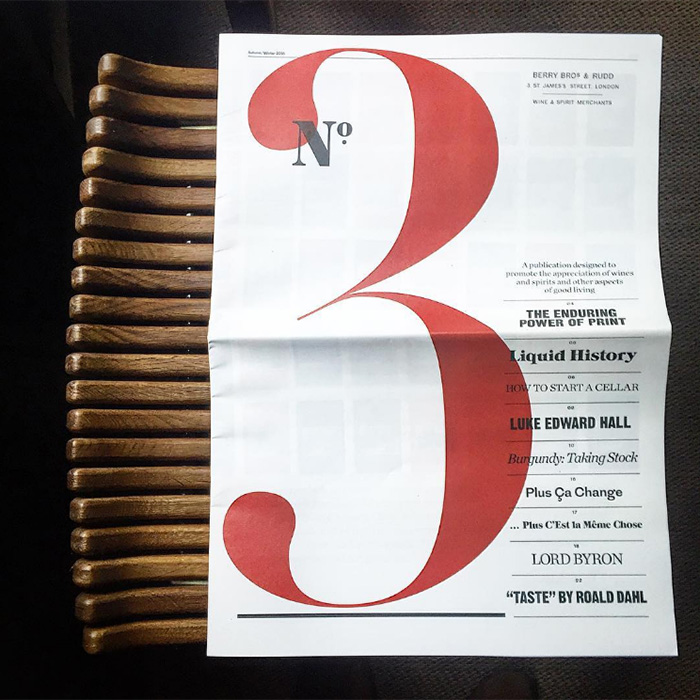

The new No.3

Finally, and most importantly, they would pick a subject for “They Came to Number Three” – a historical piece which highlighted a former customer of the firm. In almost 80 editions they ranged from Beau Brummell to Evelyn Waugh, occasionally covered groups such as the Royal Dukes (Queen Victoria’s eccentric uncles) and various artists over the years, and sometimes included luminaries of the wine world such as André Simon or Philippe de Rothschild. Almost all of these articles were actually written by Owen’s wife, Willa, who was more of a historian than her husband, and whose immaculately researched essays (before the days of Google, of course) were miniature masterpieces in their own right.

Owen would then return to Guernsey, only to reappear a couple of months later to present his efforts to my father. He was always impressed. “I don’t know how Ed does it,” he would say to me. “We chat for an hour or so, and then go in to lunch to continue the conversation. He’d scribble away in his notebook – hardly eat a thing – and then go home and produce something marvellous. He makes bricks without straw!”

I only discovered later that Owen ate so little because he was a long-standing vegetarian, but too shy to ever mention the fact to my father or the rest of the directors…

The twice-yearly format continued until 1991. At that time it was the fashion in business to pay more attention to accountants, and they began to question the costs of the exercise, and whether they could really be justified by added sales. We agreed to bring out one edition a year, half expecting that there would be an outcry from disappointed customers deprived of their biannual fix of wise words from St James’s Street. But, disappointingly, none came.

The annual publication continued until 1995. By then, times were changing very swiftly. We had already abandoned the “laundry list” for a much more readable, larger price list, complete with maps, wine descriptions, and even photographs of producers and short articles about investing in wine. We had also launched the first wine merchant’s website in the world – in 1994, way before anyone had heard of Amazon or eBay – and so much more information was at everyone’s fingertips, 24 hours a day. For a while, the magazine increased in size, but also in commercial punch. At one stage, it became something called a “magalogue” and even acquired the appalling title of Clarity. What was it Oscar Wilde said about “the price of everything and the value of nothing”? It was clear that the days of Number Three Saint James’s Street were over, and it was kindest to put it out of its misery.

All the same, the company’s publishing bent never entirely went away. In 2010 we published Jasper Morris’s definitive Inside Burgundy, which continues to sell as the pre-eminent source of knowledge in all matters Burgundian. Last year we brought out the printed version of our acclaimed wine course, Exploring & Tasting Wine: A Wine Course with Digressions. And although both publications are also available in (rather wonderful) iBook versions, the printed editions have proved much more popular.

After a few years when the publishing industry seem to be convinced that the future was digital and that print was doomed to go the same way as the Dead Sea Scrolls, the pendulum seems to be swinging back. It is reported that more books – especially hardbacks – are being bought than ever before. There is something about reading the printed word, picking up a volume, flicking through the pages, smelling the ink perhaps – that even the best designed, most brilliantly interactive e-book cannot challenge. Like wine, the real-life experience, honed and perfected over centuries of civilization, was so ingrained in us that it proved impossible to throw it away because of some passing fad.

The very first edition of Number Three Saint James’s Street, back in the Autumn of 1954, carried on its title page a sentence that summed up its raison d’etre. “This magazine is designed to promote the appreciation of wines and spirits, and other aspects of good living, against the traditional background of St James’s, London”. The last edition, and every edition between, carried the same sentence, almost word for word.

I am delighted that the magazine is back in print. May it continue to be one of the “aspects of good living” for many years to come.

Pick up a copy of No.3 in both our Basingstoke and London shops. For a flavour of the original Number Three periodical, click here.

Lucky “southernors” who can call in to the London or Basingstoke shops for No 3; but not so for those of us who live in the more remote parts of the UK.

Dear Mr McLaughlan,

They have also been mailed out to many of our customers (landing today). If you haven’t received one, please do email editor@bbr.com with your address and I’d be delighted to put a copy in the post for you.

Kind regards,

Sophie

Compliments on this exciting publication, and on the rare achievement of catching the fast-moving Mr Luke Edward Hall.

[…] an extract from No.3, Jasper Morris MW, pre-eminent authority on Burgundy, gives us a “state of the nation” […]

[…] article was originally published in No.3, our […]

[…] Luke Edward Hall’s limited-edition Good Ordinary Claret will be available to buy from 16th February on bbr.com and in both our shops. A version of this article was originally published in No.3. […]

[…] This article was originally published in No.3. […]